When I decided to embark on a career sabbatical, I knew that I wanted to spend some of my time exploring new hobbies and developing new skills. Woodworking had been something I was interested in for a long time, but my experience was limited to using a circular saw to build a set wall for a theme party. So much of my professional career is moving ones and zeros around in the cloud that I was excited to build something in the real world with my hands and then put it to use in my home for years to come. I found a woodworking class at The Cambridge Center for Adult Education, which is only a short bike ride from home. The learning process has been challenging, rewarding, and deeply humbling. Learning these new skills has given me many opportunities to reflect on how I solve new problems in new contexts and, maybe more importantly, my relationship with failure.

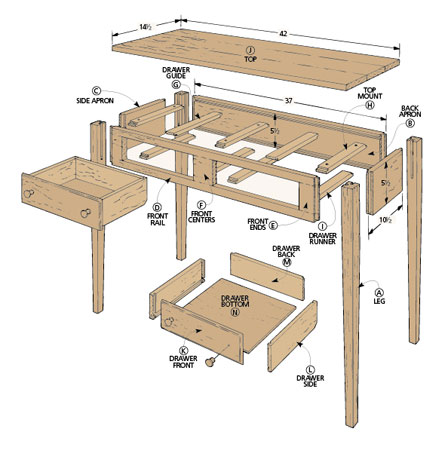

I walked into the woodworking class back in January with the expectation that I’d build some sort of Shaker table in 8 weeks. However, the instructor made it clear that his goal was to help students develop solid woodworking skills, which meant that we shouldn’t bank on having a finished product at the end of the term. We could modify plans and potentially finish, but would miss out on some skills that were really fun to learn. This was a little disappointing at first, but was ultimately was freeing. I was only just starting my career sabbatical and this became an early opportunity to prioritize rest, curiosity, and exploration over productivity, perfection, and completion. I could focus on enjoying the journey instead of speeding toward the destination. There was room to scale our projects up and down depending on our experience, appetite for learning, and aesthetic desires. As I was less focused on completion, I chose a slightly more ambitious Shaker Hall Table in lieu of the simple side table because I had a great spot for it in my apartment.

As I reflect back on these first two terms of class, there are three failures I want to explore. There were many more, but these have been the most meaningful for me. The first came as I was preparing to cut the stock pieces I purchased at the lumberyard. I found myself in a place of high uncertainty and high complexity and fell back into an old pattern of over-detailed planning that gave me a false sense of security. The second came as I was making adapting the table plans to account for some bowing in the front apron. Here I was reminded of how important it is to set up safeguards before doing things that can’t be reversed. The third came quickly after the second and was a remarkably similar mistake to the second. This ended up being a rather difficult lesson about how sometimes it takes both time and effort to internalize what you’ve learned from past mistakes.

Planning with Complexity and Uncertainty

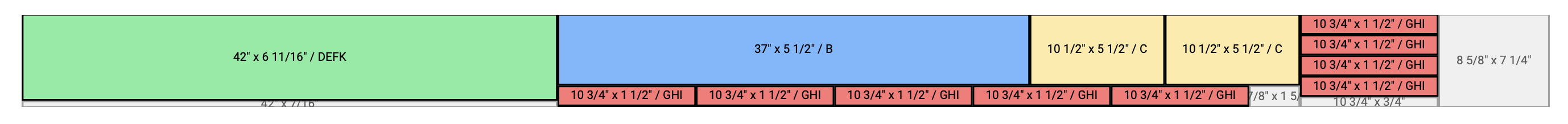

After going to the lumberyard and picking up all the stock I needed for my table, I needed to plan and cut the pieces to specification. There are a few competing goals in this stage. On one hand, you want to cut efficiently so you can minimize waste (walnut is expensive!). On the other, you want to showcase the natural beauty of the wood, as it will be perceived in the assembled table. I created a cutsheet using an online tool called Opticutter to help with efficiency. I then came into the shop with my stock and cutsheet and proceeded to spend hours painstakingly penciling out all the cuts I expected to make on each board. I accounted for the approximate width of saw blade and the grain pattern.

What I’m fairly sure that the instructor had mentioned, but I failed to internalize, was that 1) it’s important to have a little extra length on each piece as you start to work it in order to leave room for error (e.g., dropping the piece), 2) you always need to measure from a square edge, and 3) it’s really hard to draw straight lines over long distances. As I finished marking up one board and asked the instructor to review my work with me. We looked at how some lines weren’t quite straight (despite using a straight edge), how the edges weren’t square (so the lights weren’t straight), and how some edges were split (so I’d need to cut a few inches off anyway). Lucky for me none of these mistakes were irreversible. I could erase the pencil lines and start over. The only cost was in time and pride. But there was also a lot of value in this mistake.

I realized that I had fallen back into an old pattern of dealing with uncertainty and complexity through highly detailed planning. I would spend days trying to document and plan out projects with exacting task-level detail. I thought that if I could plan well enough, I could estimate time to completion with a high level of precision and avoid surprises. This approach wasn’t totally useless. It did help me think ahead and anticipate some problems and many dependencies. But, more often than not, estimates were off. Or a change in timeline or customer requirements meant throwing something out or adding something new. And everything would change, much like the pencil lines I’d drawn onto my stock wood.

As the level of detail and the time between planning activities and implementation activities increased, the probability of reworking plans also increased, often dramatically. One of my mentors, Alyssa Boehm, often talks about a similar concept with her UX teams. She is a big believer in starting with back-of-napkin sketches before building out fully detailed wireframes (or another step in between!). When you jump to the fully detailed plans with no feedback from the real world, you’ll likely have to do a lot of rework. That’s slow and expensive. Instead, your artifacts should start with juuuuuust enough fidelity to have a good conversation and to build mutual understanding. In my case, I had enough information to plan my cuts already through the cutsheet. I needed to compare the plans to the real world, get some feedback, make some adjustments, make some cuts, measure, and repeat.

Setting Myself Up for Success

One of the biggest differences between working with software and working with wood is that – and I cannot emphasize this enough – there is no undo button. On one hand, if someone had told me this before mistake number two, I probably would have looked at them with a frown and felt a little insulted. On the other hand, I hadn’t yet made a meaningful mistake that would help me understand this point not only intellectually, but also emotionally. Luckily, had the good fortune to make a few mistakes that would hammer this concept in.

The first meaningful mistake came while I was dealing with a slight bow in the front apron (face of the table) of the table. My instructor suggested that I could straighten it out by using a dovetail joint on a few of the cross-members so that it would pull the front and back aprons together ever so slightly. Having never hand-cut a dovetail before, I practiced on a few pieces of scrap wood. I wanted to reduce the cost of failure practice my skills before working on pieces that I’d invested hours into. Things were going well until I went to cut the first dovetail into the back apron. The cross-member fit into the hole I cut well enough, so I went to assemble the table with clamps so that I could measure the exact place to cut the pin on the other size of the cross-member so that it would pull the aprons together. I realized that I had cut the dovetail on the bottom of the apron instead of the top. The bad news was that this wasn’t reversible, but the good news was that it was on the interior of the table, so you wouldn’t ever see it. So, what did I learn?

Setting up systems to help yourself be successful is a critical, no matter what you’re doing, but especially in situations where reversing or reworking something is costly or impossible. This is something I did all the time as an IT professional, so I’ll admit that this mistake was rather embarrassing. Here, I was so focused on my immediate context that I wasn’t thinking about how my actions were going to affect the rest of the piece I was working on. In short, woodworking includes a lot of opportunities to make irreversible mistakes. But you can anticipate the types of mistakes you might make and then set up systems (e.g., pencil or tape markings, testing on scraps, dry assembling, asking a friend to check your work) to prevent yourself from making those mistakes – or at least minimize their impact.

Repeating Mistakes

For most of my life I’ve heard something along the lines of , “It’s fine to make a mistake as long as you learn from it and don’t repeat it.” That’s why I found myself putting down my work, leaving the shop, taking a walk, and then leaving class an hour early when I made my second mistake. This time I correctly cut on the bottom of the apron, but I can on the exterior face instead of on the interior face. As you may remember from the last section, the first dovetail I made was in the wrong place but was on the interior, so was embarrassing but immaterial to the aesthetics of the overall piece. This was on the outside of the front apron, which was the most visible part of the table, excluding the top. So, to make a similar and much worse mistake right after the first was pretty awful. Thankfully, I was able to flip the front apron such that the interior face became the exterior face. The grain wasn’t as pretty on the inside, but it did allow me to save the work and continue without having to go back to the lumberyard.

This mistake led to a few insights. First, sometimes it takes some time and practice to internalize what I’ve learned, so I may make the same mistakes right away. Only a short period of time elapsed between mistake #2 and mistake #3, so I don’t think I fully internalized what had happened and what I learned. Second, there’s only so much I can learn on the fly without taking notes and intentionally reviewing what I’ve learned. Third, I was still upset with myself for mistake #2, so I probably wasn’t in the right headspace to continue with any work that involved irreversible decisions because I wasn’t thinking clearly. What appeared at first to be making the same mistake twice turned into an opportunity to learn more about how I learn, what it takes to learn from mistakes successfully, and when I’m not in a good place to do good work and set myself up for success.

Building a Better Relationship with Failure

As a person who has been a high achiever for most of my life and who lives in a society that ties the worth of people to their productivity, test scores, and how they rank against others, I’ve been working on building a healthier relationship with failure for years. Woodworking wasn’t the first step in the journey, and it won’t be the last. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that I look forward to failure, but I do appreciate it as a valuable part of learning. Nor would I say that it’s easy, though over time it may have become easier. I’ve also come to see failure as just one indicator of my current ability and not a predictor of my potential.

I hope you’ll take the time to pick up a totally new skill every so often. And I sincerely hope that you’ll fail.